If you’ve never celebrated ‘Bloomsday’ and the name Leopold Bloom means nothing to you, chances are you’ve not read James Joyce’s Ulysses. Yet, since its publication in 1922, plenty have tried. But at a whopping 730 pages, it’s no easy task. So why does it remain so appealing? Holly Anne Crawford investigates.

When James Joyce put pen to paper to write Ulysses – a modern parallel to Homer’s Odyssey – he meant business. Seven hundred and thirty pages of business, to be exact.

The story takes place over the course of one day – June 16, 1904 – and Joyce put all of his literary prowess into recreating Dublin on the page, describing in intricate detail: the sights, smells, sounds and geography of the city, right down to the labyrinthine alleyways. Which may explain why the book runs to an impressive (or daunting, depending on your point of view) 265,222 words.

In fact, his descriptions of Dublin city are so precise that fans could use the tome as a guidebook to follow in the footsteps of protagonist Leopold Bloom who walks the streets, pondering and questioning.

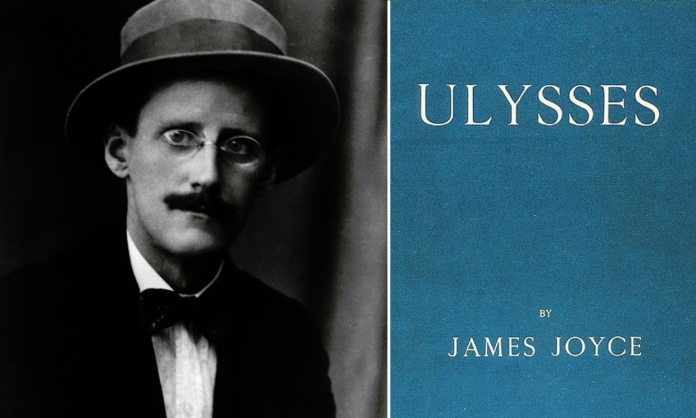

The creator of this ‘modern masterpiece’ was James Augustine Aloysius Joyce who was born on 2 February 1882 in Dublin. Described as a ‘brilliant’ student, he enrolled at the recently established University College Dublin (UCD) in 1898 where he read English, Italian and French.

Joyce dreamed of being a doctor and started studying in France but soon gave up on the idea. He returned home when his mother was unwell and earned a living singing, reviewing books and teaching.

Yet by the time Joyce published his ‘masterpiece,’ he hadn’t lived in Dublin for 13 years, meaning he was working almost entirely from memory. I find this a particularly impressive feat, seeing as I struggle to recall what I had for breakfast, let alone the geography of a place I’ve not stepped foot in for more than a decade.

Perhaps that’s part of the appeal of Joyce’s work: his ability to capture a time and place in vivid, technicolor detail. Whatever it is, it certainly endures.

But I’m just surmising. Someone better placed to tell you about the appeal of Joyce’s work is Loic Wright, a volunteer at The James Joyce Centre in Dublin.

‘‘Joyce is often credited with having put Dublin on the map of world literature. But deeper in his work is that he explored universal themes and feelings throughout his career,’’ Mr Wright explains.

‘‘Although Ulysses is praised as an experimental and innovative landmark of modernism, the plot of the novel—if it has any plot—is simply about a day in the life of Dubliners. They wake up, they eat, they laugh, cry, get jealous, get embarrassed, go to the bathroom, and go to bed. It’s a story of everyday people and emotions we can all relate to.

‘‘However, of Ulysses, Joyce also said: ‘I’ve put in so many enigmas and puzzles that it will keep the professors busy for centuries arguing over what I meant.’ ”And he was right – they continue to argue to this day.

In writing Ulysses, Joyce used a new narrative technique known as ‘stream of consciousness’ which takes readers inside the minds of characters, revealing their innermost thoughts. The final 30 (unpunctuated) pages head inside Molly’s mind and contain eight extremely long ‘sentences,’ the last running to 4,391 words, making it the longest in English Language until 2001.

Mr Wright continues: ‘‘I find Ulysses to be a time capsule, thanks to both Joyce’s meticulous eye for detail in including historical events that occurred on the 16th June 1904, as well as his keen ability to identify and replicate the cultural atmosphere of Dublin during the early twentieth century.’’

Visitors relish the chance to learn about this literary luminary and the city he loved. So much so that the Centre welcomed 22,030 visitors in 2019 alone, including reading groups from across the globe who return on a regular basis.

Even a global lockdown couldn’t diminish these bibliophiles’ passion for prose. This was proven when the Centre put many of its courses online during the Covid-19 pandemic and people from across the world logged on to celebrate their love of literature and quench their thirst for Joycean knowledge.

Mr Wright says: ‘‘Because of Ulysses’s reputation as a notoriously difficult book, many people start it, become overwhelmed and give up. An important aspect of our outreach as an educational centre, therefore, is to help people break down the barriers and obstacles associated with reading Ulysses.

‘‘Our 12-week courses break down Joyce’s novel, including key chapters, themes, characters, and important literary criticism. We also host courses on broader Irish literature to situate Joyce’s work within the wider context of Irish literary and cultural history.’’

Not only does the centre break down barriers via its courses, it also builds memories.

‘‘Everybody who visits the centre comes with their own story about how they discovered Joyce in their own corner of the world,’’ Mr Wright continues.

‘‘A couple who came to the Centre in 2019 first met in a literary modernism university class, were married on Bloomsday 2019, and spent their honeymoon in Joyce’s home city of Dublin. They booked one of the many walking tours on offer at the Centre to explore the area and left with two Bloomsday boaters, the signature Joycean hat.’’

Visitors can delve into architectural history too, as the centre is the former residence of Valentine Brown, the Earl of Kenmare. It remained his home until the Acts of Union in 1800 dissolved the Irish parliament, forcing him and many of his politician neighbours to relocate to London.

Many of the grand Georgian houses on North Great George’s Street fell into disrepair and were used to house up to 10 families at a time by new landlords. While Joyce never lived in the house, he resided in the local area in similar conditions.

By the turn of the 20th century, a room in the house was rented by dancing instructor Professor Dennis J. Maginni. Joyce includes Maginni in Ulysses as one of the many real Dublin characters he wove into his work.

It was saved from demolition by Trinity College Joyce scholar David Norris, was renovated and reopened as a museum in 1996 as a city centre complement to the Martello Tower museum in Sandycove.

Back at the Centre, staff apply their expert knowledge and interest to bring extra elements of Joyce’s work to life. For researching the music and songs which feature in the author’s work to performing them on the walking tours which, in themselves, offer a thorough insight into the city that shaped him.

‘‘The best reason to visit the James Joyce Centre, in my opinion, is to bring your own passion for Joyce’s work to a hub where you can foster your interest and discover new information about Joyce and his home city. You can see the streets named in the novels, experience the atmosphere of the city that Joyce knew so well, and talk to the Centre staff about your interests during a walking tour,’’ Mr Wright concludes.

Celebrate good tomes

Today, Ulysses is celebrated by literary circles the world over and specifically on – you guessed it – 16th June, which fans lovingly refer to as ‘Bloomsday’. There is also the popular Bloomsday Festival which takes place in Dublin during that month.

June 16th is significant because that was the day Joyce had his first official ’date’ with his future wife, the rather fabulously named Nora Barnacle, a chamber maid who, incidentally, he used as a template for Leopold’s wife Molly.

February 2nd, 2022 marks the 100th anniversary of the publication of Ulysses and there will be a host of events to mark the occasion including the XXVIII International James Joyce Symposium from 12-18 June at Trinity College Dublin.

One of the key organisers is Dr Sam Slote, Associate Professor with the School of English, Trinity College Dublin.

He said: ‘‘With Ulysses, Joyce redefines what is possible with the novel, not just in terms of style and structure, but also in terms of how human psychology is represented. If it is difficult [to read], that’s only because Joyce is trying to present humanity in all its aspects and complexities. It also has the advantage of being tremendously funny.’’

While diehard Ulysses fans will no doubt enjoy every second of The Symposium and immerse themselves in all things ‘Joycean,’ there are other ways in which novices can approach the weighty work.

Dr Slote said: ‘‘There are many courses available on Ulysses, at universities but also in terms of reading groups, some of which are formally organised, others are more informal. I do two classes on Ulysses at Trinity: a yearlong class for undergraduates and a semester-long class for graduate students. In this, Ulysses is not unique, there are classes solely devoted to other individual works of literature, such as the Canterbury Tales.’’

High society

Jonathan Goldman is currently President of The James Joyce Society which celebrates the author and his many achievements. Here, he explains its origins.

‘‘Interest in James Joyce gripped New York City’s literary world from the time his novel Ulysses started appearing serially in the Little Review, a journal published out of a Greenwich Village apartment.

‘‘The James Joyce Society…was founded in 1947, its first member TS Eliot. It met for 50 years at the Gotham Book Mart in midtown before that store’s sad demise.’’

Mr Goldman continues: ‘‘Ulysses has remained a popular book around the world for the way it suggests the infinite possibility, beauty, and depth of everyday human reality, without in any way minimizing tragedy and suffering.’’

Although he spent most of his life abroad, Joyce always returned to his hometown via his writing. Indeed, he said as much: ‘’For myself, I always write about Dublin, because if I can get to the heart of Dublin I can get to the heart of all the cities of the world. In the particular is contained the universal.’’

It would be nice to think that Mr Joyce would have been pleased to know that he has played such a major part in putting Dublin on the map and that visitors still flock to see the places he so vividly described. Thanks to his brilliant recall, fans are able to make memories of their own or at least, immerse themselves in his.

Footnote: We would like to thank The James Joyce Centre for providing the images used alongside this story.

INFORMATION PANEL

Did you know….

- Many of Joyce’s friends – and enemies – appear as characters in the book.

- James and Nora’s marriage was, by all accounts, a happy one. They emigrated to continental Europe and had two children.

- While Joyce never achieved his ambition of being a doctor, he did share lodgings with a trainee. His friend Oliver St. John Gogarty, a medical student and aspiring poet, rented a martello tower in Sandycove. He invited Joyce to join him and fellow lodger Samuel Chenevix Trench who, as it turned out, had some very unusual dreams. The trio slept in the round room on the first floor of the tower but on Joyce’s sixth night, Chenevix Trench awoke having had a dream about a black panther and got his pistol to shoot ‘the animal.’ Gogarty got the gun and let off a few rounds, hitting some pans hanging directly over Joyce’s head. The presumably petrified author fled in the middle of the night and walked eight miles back to Dublin to stay with relatives, sending a friend the next day to pack his trunk.