By John Fitzgerald

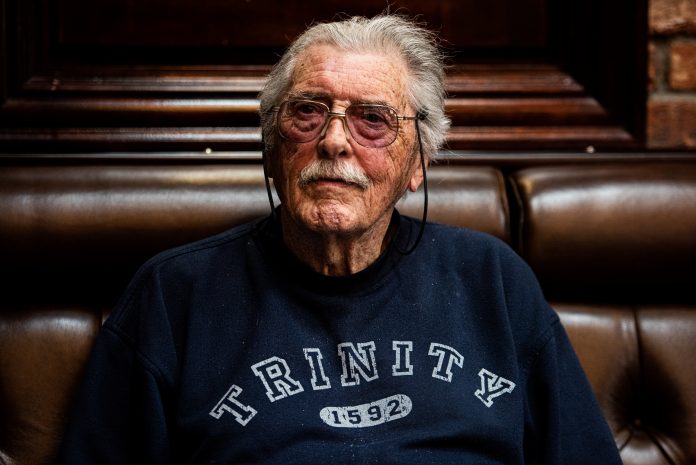

We lost another musical legend in March with the passing of the mighty Pete St John.

Phil Coulter aptly hailed him as “a gentleman, a proud Dub and a proper songwriter.” President Higgins praised him as an “indomitable source of inspiration and song.”

In his song-writing Pete caught the essence of what it means to be Irish and advocated with a rare passion the preservation of our Celtic heritage and way of life.

Born Peter Mooney in Inchicore in 1932, he was the eldest of six children. His father Thomas worked for a motor company and his mother Lotte was a gifted pianist. She saw the spark of potential in him at an early age, encouraging him to sing and to play a variety of instruments.

A teacher at the first school he attended, the local Scoil Mhuire, did likewise, and Peter began to turn heads whenever he obliged with the bar of a song in the classroom, at home, or in neighbours’ houses. A friend from childhood quipped that “Peter was something of musical instrument himself”.

After his education at Synge Street CBS he qualified as an electrician and emigrated to Canada and later the United States.

Pete returned to Ireland in the 1970s, with his wife Susan, after a twenty-year absence. He was immediately struck by the political and social changes in his native land but also by the widespread dereliction, drastic alterations to streetscapes and the disappearance of cherished landmarks he had loved as a youth and that he’d often called to mind during his long stint abroad.

This affected him deeply, and what better way to express his feeling about the downside of Ireland’s “progress” than through song. At first singing was more of a hobby, but following an injury sustained in a fall from a roof he switched his attention to song writing. For a while he ran a folk club in the Liberties that became a launching pad for his musical ideas and experimentation.

He loved ballads, and was drawn to the way they expressed the ups and down of the Irish through the long tortuous centuries of oppression, war, famine, and mass emigration. So he opted to give voice to his own lament for a different Ireland via the traditional storytelling type of song for which the Irish are renowned.

He wrote ‘The Rare Ould Times;, which struck a chord with millions of Irish people, at home and elsewhere, who felt the same “pull” of a past that was forever gone and could only be celebrated in song and poetry.

It paid homage to a bygone era, seeing its demise through the eyes of Sean Dempsey, “raised on songs and stories”, whose heart is broken by the “grey unyielding concrete” that has swept away the city of his youth.

The song went on to become a cultural phenomenon in itself, and was recorded by The Dubliners, Mary Black, and Paddy Reilly, among a host of other entertainers who brought their own styles to bear on its performance. Danny Doyle’s version endured for eleven weeks in the Irish Singles Chart in 1978.

It was an Irish answer to Joni Mitchell’s Big Yellow Taxi, except that it was Dublin’s old sights and cultural gems being feted rather than a paradise paved for parking lots. His song ‘The Ferryman’ also harked back to a vanished Ireland.

With ‘The Fields of Athenry’ Pete reached into Ireland’s dark past, telling the story of a man who faces cruel transportation for stealing corn to feed his children during the famine.

Like ‘The Rare Ould Times’, it has a melody that everyone can sing along to, and that you can’t get out of your head once you hear it.

It has been recorded by more than fifty artists, and featured in films and TV programmes. The movie ‘Dead Poets Society’ has somebody playing its catchy tune on bagpipes. Paddy Reilly’s haunting 1982 rendition was in the Irish charts for a jaw-dropping seventy two weeks.

The song went beyond being a hot favourite of every band and pub session in the country, ending up as an anthem sung at Irish rugby and soccer outings worldwide.

In later life Pete expanded his repertoire of themes to include the planetary ecosystem. His song ‘Waltzing on Borrowed Time’ articulated the multiple threats to human existence on earth better than any UN conference.

He scooped several awards for his work, including the prestigious “Irish Songwriter of the Year.”

Pete St John is survived by his sons Kieron and Brian and his soul-stirring ballads guarantee his place in Ireland’s musical Hall of Fame.