By Martin Gleeson

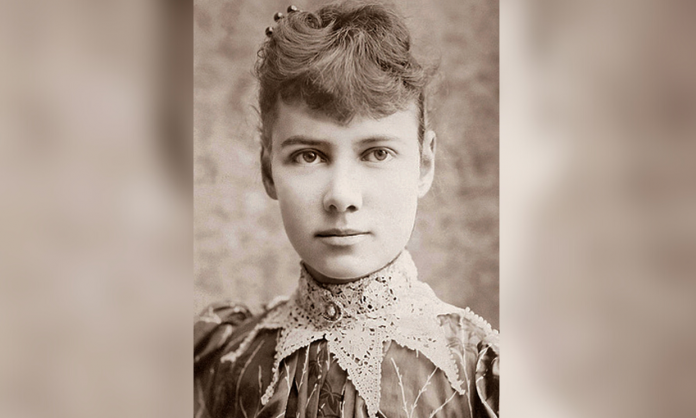

Nellie Bly was born as Elizabeth Cochrane on May 5th 1864 in Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania. The Irish have settled in Pennsylvania since pre-American Revolution days. Many settled in the booming industrial town of Pittsburgh and worked in the iron and steel mills, the mines and the railroads.

Elizabeth’s father, Michael Cochrane, was the son of an immigrant from Derry who started as a labourer but had prospered so well that he bought the local mill.

Michael Cochrane had ten children with his first wife, and five more with his second wife. Elizabeth was one of those five children.

In 1880 Elizabeth read an article in the Pittsburgh Dispatch called “What Girls are Good For.” It stated that girls were principally for producing babies and keeping house. She was so enraged that she wrote them an impassioned response. The editor was so impressed by Elizabeth’s letter that he offered her a full-time job.

In those days it was customary for lady writers to use pen names and Elizabeth chose “Nelly Bly.” This was the name of a popular song written by the great Stephen Foster. Due to a typing error Elizabeth’s pseudonym became “Nellie Bly.”

Nellie’s articles in the Pittsburgh Dispatch concerned the lives of working women, particularly those working in Pittsburgh’s many factories.

When the factory owners complained, Nellie was assigned to the fashion, society and gardening sections.

When she was 21, she decided to so something that few ladies had ever done. She travelled to Mexico as a foreign correspondent. When a local journalist was imprisoned by the Mexican government of dictator Porfirio Diaz, Nellie protested. She was then threatened with arrest and had to leave Mexico. On arrival back in Pittsburgh, she was able to accuse Diaz of being a tyrant and suppressing the Mexican people.

Nellie approached the New York World with a plan to investigate reports of brutality and neglect in the Women’s Lunatic Asylum on Blackwell’s Island. To get admitted to the Asylum, Nellie stayed in a boarding house where she stayed up all night to make herself to appear disturbed. She began to accuse the other guests of being insane and kicked up such a fuss that the police were called. When she had been examined by a police officer, a doctor and a judge, she was taken to Blackwell’s Island and locked up.

Here she experienced the dreadful conditions of the inmates. Built to house 1,000 patients, Blackwell was crammed with over 1,600. Patients were forced to have ice-cold baths and remain in wet clothes for hours. They were forced to sit on benches without speaking or moving for periods of 12 hours or more. Some were tethered together with ropes and forced to pull carts around like they were mules. Rotten meat, mouldy stale bread and often dirty water were served. Anyone who complained was beaten.

Foreign patients who could not speak English were treated with great hostility.

Nellie saw that many of the patients in Blackwell were not insane, but ending up committed there simply for being poor, with no family to support them. After ten days her newspaper secured her release.

Nellie wrote a book called ‘Ten Days in a Mad-House’ which caused a sensation.

Nellie’s revelations about the asylum caused a grand-jury panel to visit the institution. The staff had been tipped off in advance and the asylum had been cleaned and many of the inmates that had been horribly treated had been released. Nevertheless, the grand-jury panel agreed with Nellie’s opinion and $1 million of extra funding was allocated. Abusive staff were fired, and conditions were improved.

Nellie suggested to her editor of the New York World that she take a trip around the world, attempting to follow the fictional trip in the 1873 novel ‘Around the World in Eighty Days’. On November 14th, 1889, Nellie boarded the German ocean liner Augusta Victoria in Hoboken, New Jersey, taking only her travelling gown and coat, and a satchel that measured just 16 by 7 inches. She experienced seasickness but mingled with the other passengers. Eight days later the ship landed in Britain and Nellie travelled by train to London where she viewed the sights.

When she reached Folkestone, she took the ferry across to Boulogne. While in France she made a detour to see her the author of ‘Around the World in Eighty Days’, Jules Verne. When she visited him in his house, Nellie used a translator to have a detailed conversation with him about the best way to travel around the world. Saying goodbye to Verne, she headed for Calais to board the mail train to Italy.

Taking the steamship Victoria, Nellie sailed to Port Said, and then to Aden where she marvelled at the small boats with traders trying to sell their wares. When she reached Colombo in Ceylon (now Sri Lanka) Nellie stayed in style in the Grand Orient Hotel. She enjoyed their tiffin, a midday meal. She had time to visit the city of Kandi, the site of the Temple of the Sacred Tooth Relic, which contains a tooth of Buddha. In Colombo Nellie changed ship to the Oriental which sailed to the island of Penang and in its capital George Town she visited a Hindu temple.

Nellie’s next stop was Singapore where she viewed the Raffles Library and Museum, St. Andrew’s Cathedral and Cavanagh Bridge. A stormy sail south on the Oriental brought Nellie to the Crown Colony of Hong Kong. A week’s delay in Hong Kong gave Nellie an opportunity to explore the city and to travel to the top of Victoria Peak where she enjoyed the view of Kowloon Bay. She took an overnight ferry to the city of Canton, where a Chinese man greeted her by saying “Merry Christmas”. She had forgotten that it was December 25th.

When Nellie resumed her travel again, she sailed to Yokohama, in Japan on the RMS Oceanic. On board this comfortable ship on midnight on New Year’s Eve, she was able to herald in 1890 by singing “Auld lang Syne”. Nellie had to spend a week in Japan waiting for her ship to bring her to New York, so she visited Tokyo to witness how Japan was been modernised. She noticed that the city had a streetcar line, an extensive railway and streetlights. One evening she went with some of her ship’s companions to a geisha house and she found the geishas enchanting.

Before Nellie left Yokohama, press coverage of her world trip had made her famous in the USA, and the band of the USS Omaha played a short concert in her honour and wrote a little couplet for her: For Nellie Bly, We’ll win or die. Sailing across the Pacific Ocean on the Oceanic, Nellie was one of the 167 first-class passengers. Also travelling steerage on the ship were hundreds of passengers crammed together in the lower decks. Many were Chinese migrants going to America for work.

On January 21st 1890, Nellie reached San Francisco.

As Nellie started her trans-America rail journey, snow caused delays in California.

At every station, people who had read about her exploits greeted her with great admiration. During as short break in Chicago, she visited the Chicago Board of Trade where the brokers gave her wild applause. On January 25th, Nellie’s train arrived at the Jersey City station, marking the end of her round the world journey in 72 days, 6 hours. She had created a world record. 15,000 people were there to welcome her back.

For a large part of her world journey, Nellie had been unaware that another journalist named Elizabeth Bisland had started on the same journey in the opposite direction. Without knowing it, Nellie had been in a race! This race was covered with great excitement by the world press.

Nellie was the winner as Elizabeth Bisland took four days longer to get home.

After her hectic around the world trip, Nellie decided to write serial stories in a New York weekly newspaper. She also wrote eleven novels. She often did lecture tours, speaking about her travels.

In 1895 Nellie married a millionaire manufacturer named Robert Seaman. Due to her husband’s bad health, Nellie left the field of journalism to manage her husband’s Iron Clad Manufacturing Company. The company did well for a while producing steel barrels and garbage bins but eventually ran into financial trouble.

At the outbreak of the First World War, Nellie re-entered the world of journalism and became a war correspondent in Poland and Serbia. Nellie had been an avid supporter of women’s rights and she lived to see the passage of the 19th amendment to the American Constitution, giving women the right to vote.

Nellie Bly, who real name was Elizabeth Cochrane, was a pioneer journalist, a world traveller and industrialist, died of pneumonia in New York City in January 1922.