By Joe Kavanagh

On a September day in 1853, Robert Schumann answered the door of his Düsseldorf home to a small, blonde, blue-eyed young man of twenty. His name was Johannes Brahms, and like Schumann, he was also a composer, although not nearly as well known. He had come all the way from his home in Hamburg to ask the great man to listen to his music. Schumann invited him in, sat him at his piano, and asked him to play.

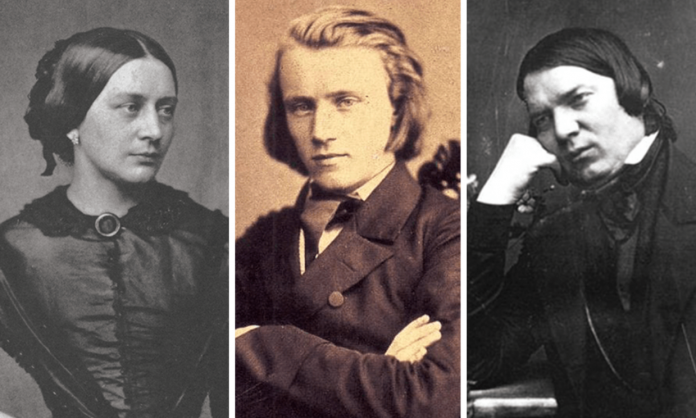

After listening to just the first few bars, Schumann could not believe what he was hearing. He stopped the young man briefly, telling him, “My wife must hear this!” He called his wife Clara, who was a concert pianist and composer, and just as famous as her husband. Together they listened enraptured as Brahms continued playing his music. That evening, in their respective diaries, both husband and wife were effusive in their praise of the young stranger, with Clara noting that he “seemed as if sent from God”.

The story of how the lives of these three musical geniuses became intertwined is a fascinating one. Robert Schumann was born in 1810 in Zwickau in eastern Germany, the son of a bookseller and publisher. Having such easy access to books, he became an avid reader, and was also given piano lessons. He began composing at the age of seven. His father died when he was 16, and two years later, his mother pushed him into law school at Leipzig University. Schumann however had no interest in law.

He spent most of his time playing the piano and writing songs, inspired by the music of Franz Schubert, whom he greatly admired. He also began to study music under Friedrich Wieck, a noted piano teacher. Wieck had a 9-year-old daughter named Clara, who was a prodigy on the piano, and who Wieck would take on concert tours.

After a year’s break spent at Heidelberg University, where he devoted most of his time to drinking and socialising, Schumann finally quit his law studies and returned to Leipzig, resuming his studies under Wieck. He had high hopes of becoming a virtuoso concert pianist, but an injury to his right hand forced him to abandon this dream and to concentrate on composing instead.

He was also interested in writing, and after a deep spell of depression following the deaths of some family members, he founded a magazine called Die Neue Zeitschrift für Musik (The New Journal for Music) in which he wrote critical articles on music and composers.

In 1834 he became engaged to 16-year-old Ernestine von Fricken, another of Wieck’s pupils, but broke off the engagement the following year. He was by this time becoming more and more attracted to Clara, who was now 16, nine years his junior, and she returned his affections. He proposed to her when she was 18. Wieck was furious when he learned of this, as he disapproved of Schumann’s drinking and considered him reckless and irresponsible. It is also likely that he was thinking of the income he would lose as a result of no longer being in charge of Clara’s concert tours. He refused to give his consent to the marriage and promptly banned Schumann from seeing Clara, although the lovers continued to meet in secret whenever they could.

The matter eventually ended up in the courts, which decided in favour of Schumann and Clara, and allowed them to marry. They were wed on September 17, 1840, ironically the day before Clara’s 21st birthday, when she would have been free to marry anyway, with or without her father’s consent. They would go on to have eight children, one of whom died in infancy. Two years after the marriage, Wieck reluctantly became reconciled with the couple, as he wanted to see his grandchildren.

During this time, Clara became a great source of inspiration to her husband, and as he was no longer able to perform due to his injury, she effectively became his “playing hands”, performing his works in concerts. They toured extensively throughout Europe, something which Clara enjoyed a lot more than Robert, who felt he was becoming a kind of celebrity husband, living in his wife’s shadow. He also preferred quietness and solitude for his composing.

In 1850, Schumann moved to Düsseldorf to take up a position as director of the city’s symphony orchestra, but left following complaints about his conducting. It was shortly after this that Brahms made his aforementioned dramatic entrance into the lives of the Schumanns, having as yet not achieved any great acclaim as a composer.

Born in Hamburg in 1833, he had had piano lessons from the age of seven, but although showing immense promise, he had frustrated his teachers by showing more of an interest in composing than playing. By the age of 20, he had written some works under a pseudonym. A friend, Joseph Joachim, who was a noted violinist, gave him a letter of introduction to Schumann. Following the hugely favourable impression that he had made on them, Robert and Clara invited Brahms to stay at their home for a few weeks, and promised to promote his career. Schumann wrote an article in his magazine, highly praising this young talent, and this led to the first publication of Brahm’s works under his own name.

In 1854, Schumann began to suffer hallucinations and nightmares, and tried to drown himself in the Rhine, but was rescued by some fishermen. He was taken to an asylum at Endenich, near Bonn. Brahms moved into the Schumann home to help Clara, who had seven young children to rear, and he became a great source of support and strength to her, often visiting Schumann in hospital on her behalf, as she was not allowed to do so, on doctors’ orders. On July 29, 1856, Schumann, whose mental illness many believed was due to syphilis contracted in his reckless youth, died of pneumonia at the asylum. He was just 46 years old.

By this time, Brahms had become totally infatuated with Clara, who was fourteen years his senior, but still a very attractive widow in her mid-thirties. After Schumann’s death, they took a break in Switzerland with the family. They were now free to marry, but whatever happened on the Swiss holiday, they decided to go their separate ways, Brahms returning to Hamburg and Clara to Düsseldorf. We know of Brahm’s adoration of Clara from his letters to her, which survive, but it is unclear whether or not she returned his feelings, as Brahms destroyed all her letters to him. It is unlikely, however, as she was devoted to the memory of her beloved Robert whom she was to outlive by forty years.

Brahms and Clara remained firm friends for the rest of their lives, keeping in touch and often holidaying together at Lichtental in Austria, where Clara kept a cottage. She continued to support his career by including his music in her concerts, thus setting him on the road to the huge success that he was to achieve. Brahms never married, despite being involved in one or two brief relationships in the years that followed.

When Clara died on May 20, 1896, at the age of 76, Brahms was devastated. He was on holiday in Salzburg at the time, and took the train to her funeral in Frankfurt, arriving late only to find that her remains had been brought to Bonn, to be interred alongside her husband. After another train journey, he arrived at the cemetery just in time to join the funeral cortege. He told friends, “Today I have buried the only person I ever truly loved.” Brahms by this time was himself seriously ill with cancer, and died on April 3, 1897, having survived Clara by less than a year.

The lives of Robert and Clara Schumann and Johannes Brahms will continue to be inextricably linked as long as music is played and enjoyed. Their story adds a deep humanity to the classical music narrative. It is to be hoped that these three gentle souls are still making glorious music together with the angels.