By John Scally

I love the story that when someone handed Mick O’Dwyer an orange, the youngster thought it was a football, as oranges were scarce in wartime Waterville, and gave it a kick down the road.

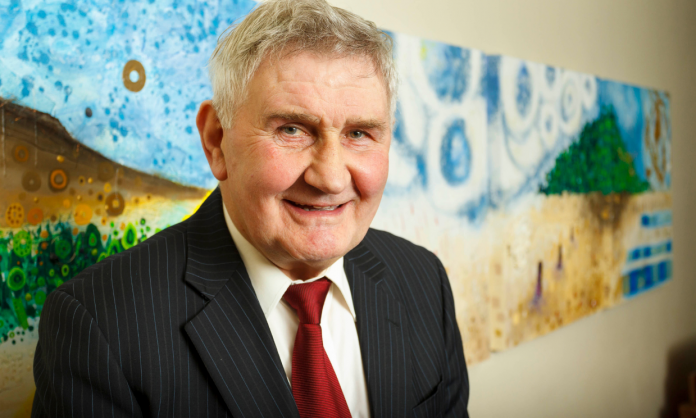

A neighbour once asked him if he had ever been to Lourdes? O’Dwyer responded: ‘Did Kerry ever play there?’ Mick O’Dwyer is universally acknowledged as the greatest Gaelic football manager of all time because of his achievements of winning eight All-Irelands with Kerry, two Leinster finals with Kildare and a Leinster final with Laois. In 2007 he marked the occasion of his seventieth birthday by becoming manager of Wicklow, where yet again he sprinkled his magic dust and transformed them from being ranked the second worst team in the country to the dizzy heights of a place in the top 12 in 2009. Despite a rare health setback O’Dwyer continued to coach the squad during the summer of 2007.

Many managers career statistics have been grossly distorted by an addiction to the game that caused them to go on managing far past their prime. O’Dwyer though maintained his unashamedly romantic vision of what his team could accomplish on the pitch, his insistence that they could not settle for simply winning matches but must try to fill every performance with flair, verve and originality. Even without his achievements as a manager O’Dwyer would be guaranteed his place among the GAA immortals because of a glittering playing career: winning four senior All-Ireland medals and eight League medals.

His early days in the green and gold jersey were not without disappointment. He played minor football for Kerry against Waterford in the Munster championship and was replaced, to his great surprise, in the next match by Ireland’s favourite poet Brendan Kennelly, who recalls the incident with amusement: “O’Dwyer told me that I would never amount to anything because my togs were too long! I heard though he told someone else that I would never make it because my bum was too close to the ground.” O’Dwyer though made up for lost time and in his 18 years on the senior team and was chosen as footballer of the year in 1969. Shortly after he retired he took over a young squad and quickly turned them into the greatest football team we had ever seen until Jim Gavin’s Dublin came along.

Match of the Day

The 1977 All-Ireland semi-final is often spoken of as the greatest game of all time as two great teams went toe to toe with Dublin eventually coming through.

In conversation with this scribe Jimmy Deenihan offered an anatomy of the most successful trainer in history, Mick O’Dwyer who had his nadir in that semi-final.

“He was very discerning. He could look at a player and know if he was drinking. He was a great judge of a player’s condition. He could smell the drink of an individual. If he thought people weren’t serious he would crucify them in training and give extra to anyone not toeing the line. He had a good understanding of people. Some would call it cunning. He was quick to make his mind about someone and if you entered in O’Dwyer’s confidence you had a supporter for life. He could read your mind and he could detect when someone was not sincere. He punished mediocrity.

“He nearly lost his job after we lost that semi-final. In Kerry there is very little tolerance for failure. We had lost to the Dubs two years in a row. Micko was wounded by the criticism and it hurt him deeply but he was not going to tolerate a third year of failure. He showed the next year that he had learned a lot of lessons from that defeat. People speak of it as a great match but for me it was a seminal moment in the development of that Kerry team. We were going to put things right after it and O’Dwyer had us primed to crush the Dubs. It was real rivalry and both teams pushed each other to get the best out of themselves. Dublin won that battle but in the long term we won the war.”

Pat’s Perspective

Pat Spillane is not convinced that the Dublin-Kerry rivalry was a completely positive thing for the GAA. “Everyone thought Kerry and Dublin won in the 1970s and 1980s because of frightening physical regimes. This was actually incorrect but it was a good rumour to throw out at the time. Everyone aped us.

What is even worse is that fellas with no knowledge of football earned a great living by training teams at intercounty level and even more alarmingly at club level driving players into the ground, running. When people heard about these tough regimes they said knowingly, ‘Isn’t he a mighty man.’ Two things happened as a consequence. The standard of football dropped alarmingly because we were producing athletes and runners rather than footballers. The second thing is that these men are responsible for the huge number of crocked ex-players who are the result of that intensive training from these years.

“Too many teams are like sheep. They follow the crowd. If one team does a hundred laps a night, the next one has to do 120 laps. If one crowd trained up a 100 metre hill the next found a 200 metre hill and then the next had to climb a mountain. When one crowd goes for a swim, the next has to swim in a lake and the next go swimming in the sea.” Pat Spillane though is much more positive when asked to assess the merits of that Kerry team. “Micko’s great Kerry side were the prototype of the successful team.

They had the four obvious things: they were fit, they trained hard, were talented and gave one hundred per cent. They had six other ingredients though that made them so successful. Firstly, they never depended on one or two individuals to produce the goods. If Mike Sheehy and the Bomber were having an off day the likes of John Egan and Ger Power produced big performances. Secondly, they were very much a team.

“Mick O’Dwyer did not want to see any one come off the field happy after a defeat. There was no point in saying, ‘I played well but the others let me down’. O’Dwyer always drilled into us that we won as a team and we lost as a team. Thirdly, they were able to handle success – not after ’75 but after the defeats of ’76 and ’77 they were equipped to do so. They used this capacity to motivate themselves to achieve even more success.

They enjoyed it when it came but they knew it was just a brief interlude unless they came back and won again the following year. Fourthly, they had a positive attitude. Each of them always believed that they would beat their man even when they were marking a more skillful player and collectively as soon as they put on the Kerry jersey they believed no team would beat them. That is not arrogance but positive thinking.

“Fifthly, the Kerry players were very intelligent. It is vital to a team to have players who think about the game, especially about improving their own game but in particular players who can read a match and when things are going badly never lose their composure and can turn things around. Sixthly, they had inspired leadership from Mick O’Dwyer. His man-management skills were excellent, he instilled belief and got them right physically and mentally for the big day.

He also knew how to motivate them. When it comes to motivation it is different strokes for different folks. Dwyer knew what buttons to push to motivate them individually and collectively. He always provided the team with good feedback. It was always positive feedback, which was more effective than negative. Above all he was a winner. Winners have critical skills, do not leave winning to chance, leave no stone unturned and make things happen.”

Simplicity is Genius

Pat Spillane is ideally placed to analyse Micko’s success. “Nowadays players have diet plans and schedules for the gym. In our time when we won the All-Ireland in September we weren’t seen again until March or April. Micko did have a problem with what were termed ‘the fatties’ on the team who put on weight. He would bring them back earlier for extra training.

He would always have a few rabbits or hares to set the pace for them. The interesting thing though was that there never was a complaint from them. O’Dwyer’s final year with Kerry came in 1989 after three successive defeats to Cork in Munster finals. That year he thought he could get one last hurrah out of the team. It is probably the six million dollar question for a player or a manager coming to the end of their career: is there one last kick in the team?

“That year Dwyer felt the only way he could eke out one last title from us was if he had us all really, really fit. He had us training in a little all-weather track in the Kerins O’Rahilly pitch in Tralee. We ran and we ran and we ran.

It is one of the rare mistakes he made. Unfortunately all of our energy was left on the training field and when it came to games we had nothing left in the tank. It was not that he was great on tactics. He wasn’t but like sex, the movements in Gaelic football are somewhat limited and predictable and tactical genius isn’t everything. His real talent was that he was a great man-manager.’

Morale booster

Pat Spillane is keen to trumpet O’Dwyer’s skills as a psychologist: “Dwyer’s key to success was man-management. He made you feel that you were the greatest. The other secret was motivation. He realised early on that medals weren’t the thing. He always dangled carrots. He started with holidays and then moved on to better holidays. He is a loveable man, driven by football.

Football is in his blood. It is his fix. What people forget is that competition for places on that Kerry team were ferocious. You knew that if your standards dropped you would find yourself on the sub’s bench. O’Dwyer was a great man for keeping you on your toes. From time to time that meant suggesting that particular subs might be moving up the pecking order. Of course if that was true someone on the first team would have to lose out and everybody was determined it wasn’t going to be them so the pace of training was upped.

Micko had a kind of aura about him that made players want to earn his favour, and a completely natural, straight-from-the-heart sense of how to inspire players. He was able to bring the best out of his gifted but sometimes difficult stars.”