By Gerry Coughlan

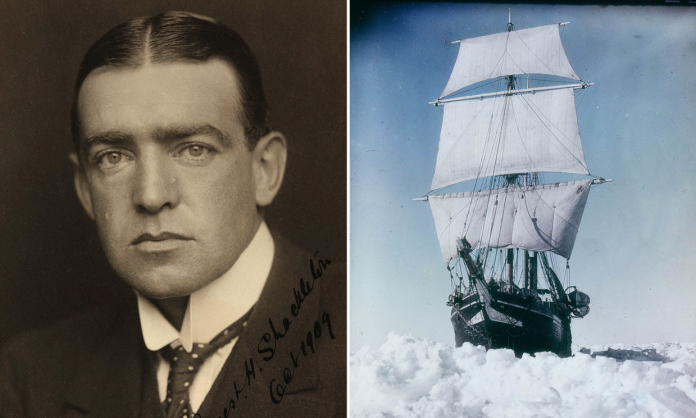

Ernest Shackleton’s ship ‘Endurance’ was finally found by an expedition team from the Falkland’s Maritime Heritage Trust on 5 March 2022, 100 years to the day since Shackleton was buried. It was crushed by Antarctic ice and sank some 3,000m to the ocean floor more than a century ago, laying 3,000 metres on the Antarctic seabed in near perfect conditions for 107 years.

Sitting agog I watched a video released by the exhibition. However, the Endurance22 mission, organised by the Falklands Maritime Heritage Trust and using advanced underwater vehicles called Sabertooths fitted with high-definition cameras and scanners, tracked the vessel’s remains down.

As the stern of the ship loomed out of darkness, the outlines of the wooden rails are soft with algae, and one pale, ghostly anemone clings to the planks. As the camera moved closer, the shape of a star rose up from the gloom and a word on the ship beneath the anemone’s white fronds becomes legible. Footage showed the ship in pristine condition with ‘Endurance’ clearly visible on the stern.

Nothing was touched on the wreck. Nothing retrieved. It was surveyed using the latest tools and its position confirmed. It is protected by the Antarctic Treaty. The three-masted sailing ship was lost in November 1915 during Shackleton’s failed attempt to make the first land crossing of Antarctica.

Previous attempts to locate the 44m-long wooden wreck, whose location was logged by its captain Frank Worsley, had failed due to the inclement conditions of the ice-covered Weddell Sea under which it lies. “We are overwhelmed by our good fortune,” said Mensun Bound, the expedition’s Director of Exploration.

“This is by far the finest wooden shipwreck I have ever seen. It is upright, well proud of the seabed, intact, and in a brilliant state of preservation. “The expedition led by British polar explorer John Shears operated from the South African ice-breaking ship Agulhas II and also researching the impact of climate change – found the “Endurance” 6km from the position recorded by Worsley.”

Despite being stranded on ice, the 28-man crew of the ‘Endurance’, including Kerry man Tom Crean, made it back home alive and theirs is considered one of the great survival stories of human history. They trekked across the sea ice, living off seals and penguins, before setting sail in three lifeboats and reaching the uninhabited Elephant Island. From there, Shackleton and a handful of the crew rowed some 1,300km on the lifeboat James Caird to South Georgia, where they sought help from a whaling station. On his fourth rescue attempt, Shackleton returned to pick up the rest of the crew from Elephant Island in August 1916, two years after his Imperial Trans-Antarctic Expedition left London.

Ernest Shackleton was born on 15 February 1874, in Kilkea, County Kildare. His father, Henry Shackleton, applied to join the British Army, but was stymied from doing so on health grounds, becoming a farmer instead, settling in Kilkea. The Shackleton family hailed from Yorkshire. Abraham Shackleton, an English Quaker, moved to Ireland in 1726 and was schooled at Ballitore, County Kildare. Shackleton’s mother, Henrietta Letitia Sophia Gavan, descended from the Fitzmaurice family. Ernest, the second of 10 children became a voracious reader, which sparked a passion for adventure. Schooled by a governess until 11 when he started at Fir Lodge Preparatory School in West Hill, Dulwich, London. Aged 13, he entered Dulwich College, and in his final term at school he achieved fifth place in a class of 31.

Tom Crean’s granddaughter, Aileen Crean O’Brien said: “To see the footage this morning, it was just amazing. I mean it’s pristine. It makes the hair stand up on the back of your neck. And to think that our grandfather, Tom Crean, stood at that wheel over a hundred years ago, it’s just fantastic, it’s brilliant news.”

Welcomed by the Ernest Shackleton Museum in Athy, Seamus Taaffe, a director of the museum, said of the news: “We’re beyond excited, we’ve been promoting the story of Shackleton’s life and his expeditions over the last 20 years and I suppose we hoped against hope that the day would come when they actually would find his Endurance ship, the ship that’s at the centre of the greatest story in his exploration life.”

On Shackleton’s return home, public honours and state preferment abounded. King Edward VII elevated him to a Commander of the Royal Victorian Order. In the King’s Birthday Honours, he was knighted becoming Sir Ernest Shackleton. Honoured by the Royal Geographical Society, he received a gold medal. All the members of the Nimrod Expedition shore party received silver Polar Medals with Shackleton receiving a clasp to his earlier medal.

In 2016 a decision to erect a monument in honour of the explorer in Athy, near his birthplace at nearby Kilkea, was opposed by Sinn Féin on the basis that Shackleton was “a British climber” and the statue “a monstrosity”.

Happily the bronze statue was erected and stands 6ft tall in Athy’s Emily Square.

If polar landscapes make us contemplate the vastness of space, polar wrecks make us contemplate the vastness of time. There is something bracing about knowing there are parts of the world where time hardly passes; that a ship can sit in perfect cold and silence, untouched by anything but salt and silt for 107 years. It’s like looking at a diamond: evidence of the inconceivable expanse of time, cold and beautiful.