Westmeath man talks about his experience of flying Concorde

By Risteárd Ó hÓgáin

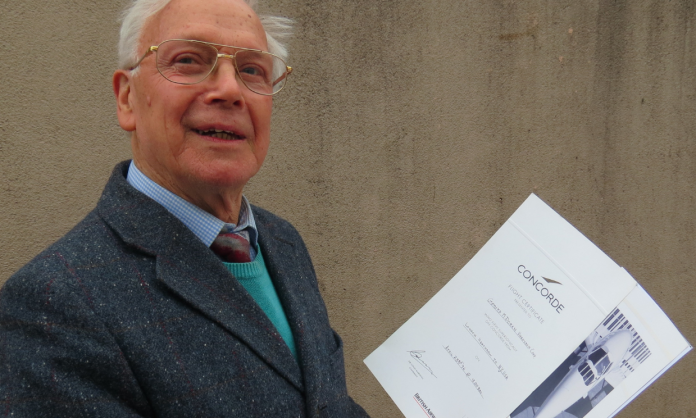

It’s seldom you meet someone who has travelled from Heathrow in London to New York and back again, in the space of just seven hours, but recently I discovered that a man and his wife in Mullingar, Co. Westmeath did exactly that – and they have the official certificates to prove it.

Though retired now for some years, Gerry Doran, a Castlepollard man who has lived in Mullingar for decades, is well known in the town because of his close involvement in establishing its first piped television service. But not very many know that he and his wife achieved something unique in the 1990s – after he had won the “flight of a lifetime” – what the organisers called a ‘Champagne Flight for Two on Concorde’.

It was while chatting to him about his work in decades past in the world of television, when he was describing how Mullingar was probably the first town outside Dublin to have a piped television service, that he mentioned how at one stage, while he was working as a designer/engineer for a London-based company Videotron Corporation, back in the 1990s, he and his wife had travelled from London to New York and back on a British Airways Concorde.

“I needn’t tell you it was a prize I won, otherwise we wouldn’t be flying Concorde!” he laughed, describing how he learned in November of 1995 of his win, and the flight took place in April 1996.

Gerry still has the official Concorde Flight Certificates signed by the Captain and presented to him and to his wife Maureen, describing how they had flown “supersonically on Concorde from London to New York on April 23, 1996”.

At that time, a ticket on Concorde from New York to London cost something like $7,995 and the equivalent in sterling, so we could readily understand when he described how it was mostly the wealthy who travelled on the supersonic passenger airliner and they received special treatment on the occasion.

“Some people find it hard to believe, especially how we could have travelled to New York and back in seven hours, even on the supersonic Concorde,” he explained, “but for whatever reason, we didn’t land in New York. The aircraft turned around and after leaving at 1pm on that day, we were back in London while there was still daylight,” he recalled.

The Castlepollard man didn’t think that two-way flight had created any kind of record, but with a cruising speed of Mach 2, or 1,350 mph (2,200 kmh), a time of around seven hours for the journey definitely made it the “trip of a lifetime” for Gerry and Maureen Doran.

What was it like travelling at twice the speed of sound, we asked, and Gerry Doran said what he noticed most was that because the supersonic aircraft had a cruising altitude of close to 60,000 feet, it was flying so high that “you were looking up at a dark blue colour”, almost as if you were up in space.

He was allowed into the cockpit of the aircraft, and took a few photos there.

What he is also aware of is that the opportunity they got to fly on the supersonic Concorde was special, from another viewpoint, because less than a decade afterwards, there was no longer an opportunity for anyone to take a flight on a supersonic airliner. Commercial supersonic travel came to an end in late 2003, having begun 27 years earlier, in 1976.

The development of supersonic airliners was a joint venture begun in the 1960s involving both Britain and France, and both British Airways and Air France were flying Concordes from 1976 onwards.

The two companies blamed rising maintenance costs and low passenger numbers for the decision to de-commission Concordes in 2003.

One fatal crash in July, 2000 definitely contributed to the fall in passenger numbers flying Concorde thereafter, but getting enough people to use the supersonic aircraft and pay the modern equivalent of more than $12,000 for a transatlantic flight, no matter what luxuries or extras were offered, was a real problem.

The one fatal crash, when an Air France Concorde crashed minutes after take-off in Paris, was enough to become a fatal blow.

“So even today, more than a quarter of a century after we were flown to New York and back in seven hours, the most modern of commercial aircraft are not yet flying at supersonic speeds,” Gerry Doran remarked.