By Alison Martin

Following Sinn Féin’s landslide victory in the 1918 General Election, the new Dáil met for the first time in January 1919. During the two-hour sitting held in the Mansion House, Dáil members adopted a Constitution and read out a Declaration of Independence. This declaration reaffirmed the Republic which had been proclaimed in 1916. A message was also issued ‘To the Free Nations of the World’. The Department of Foreign Affairs was one of the departments established by the Constitution of the First Dáil.

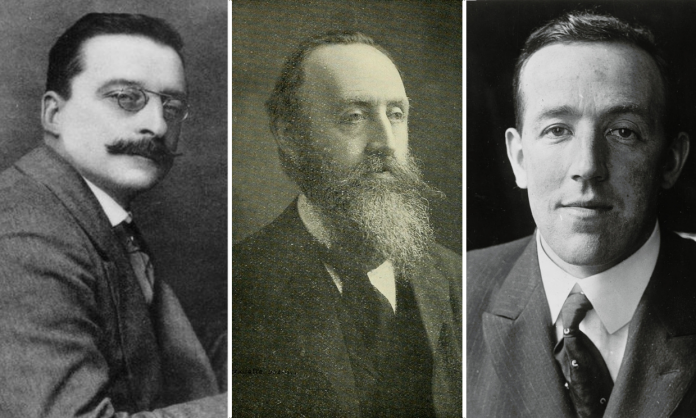

International recognition of the Republic was one of the Dáil’s main priorities. Interestingly though, the scholar Gerard Keown noted that there was also a desire ‘to breach what Arthur Griffith had described as the paper wall which had been erected around Ireland in the hundred years after the Act of Union.’ Count George Noble Plunkett was appointed Minister for Foreign Affairs in January 1919. However, he was merely a figurehead. Diarmuid O’Hegarty, Secretary to the Dáil Ministry, handled most of the correspondence dealing with foreign affairs. By June 1920, Plunkett’s status had been reduced to that of Associate Minister for Foreign Affairs.

One of the first international steps taken by the Dáil, was to send the speaker Seán T. O’Kelly to Paris, in order to make contact with the American President Woodrow Wilson. He was instructed to ask Wilson to obtain permission from the British government, for an Irish delegation consisting of de Valera, Arthur Griffith and Count Plunkett to attend the Paris Peace Conference.

It was hoped that Wilson would support Irish self-determination. O’Kelly was later joined by George Gavan Duffy, Joseph Walshe, Seán Murphy and Michael MacWhite. None of the aforementioned had any formal diplomatic training, nevertheless they did have desirable qualities. Walshe had studied law at UCD and was an excellent linguist. Seán Murphy had also undertaken legal training whilst MacWhite had served in the French Foreign Legion from 1914 until 1918. Ultimately, Wilson refused to meet the Irish delegation in Paris. Nevertheless, the envoys did gain publicity for the Irish cause.

The efforts to gain recognition of the Republic were spread across Europe. O’Kelly controlled a network of envoys. John Chartres for instance, was active in Berlin while Gerald O’Loughlin worked in Denmark. Dáil propaganda was particularly effective in Rome, where George Gavan Duffy and his wife succeeded each other as representatives. However, Paris remained a key diplomatic centre until 1922.

After the failed attempts to get a hearing at the Paris Peace Conference, the focus of the Dáil’s foreign policy shifted towards America. The President of the Dáil, de Valera, placed a high level of importance on propaganda and foreign affairs. Assisted by Harry Boland, he toured America from June 1919 until December 1920. The aim of this mission was to gain recognition of the Dáil.

Another of the Dáil’s foreign policy aims, was to raise funds to finance the revolutionary government and its foreign missions. In 1920 a bond drive was launched, headed by James O’Mara, who had been sent to America in order to take charge of fundraising. Within six months, $5.5 million had been raised. However, little of this actually got back to Ireland. De Valera failed to get official recognition of the Republic from the American government but his visit had been a successful propaganda exercise. This was in itself a very important aspect of the Dáil’s foreign policy.

In February 1921, de Valera appointed Robert Brennan as the Under-Secretary for Foreign Affairs. It would seem that there was an ulterior motive behind this. Indeed, de Valera hoped that the appointment of Brennan would allow him to exercise more influence over the department and eventually outmanoeuvre Plunkett. De Valera and Brennan drew up guidelines for the organization of the diplomatic service. Irish representatives abroad would now be expected to send monthly reports on their work. Loyalty to the ministry and its policies was also insisted upon.

These reforms marked the beginning of the professionalization of the diplomatic service. After a truce in the War of Independence was declared on the 11th July 1921, the Department of Foreign Affairs was able to operate without the threat of being raided by the British forces. Moreover, interest in Sinn Féin diplomats increased, as prior to the truce some countries had been afraid that communication with Irish representatives would harm their relations with Britain.

When the Anglo-Irish negotiations began, de Valera was unable to devote much time to foreign affairs. Arthur Griffith replaced Plunkett as Minister for Foreign Affairs on the 26th August 1921. The Anglo-Irish Treaty was signed in December 1921 and on the 7th January 1922, the Dáil accepted it by sixty-four to fifty-seven votes. Griffith was elected President following de Valera’s resignation. The scholar Michael Kennedy observed that ‘over the next few months the Treaty was to be the downfall and almost the death of the Irish foreign service.’ This is certainly an accurate observation.

The Treaty divided the infant diplomatic service, as many of the most experienced foreign representatives opposed it. George Gavan Duffy, who replaced Griffith as Minister for Foreign Affairs on the 10th January 1922, was given the unenviable task of attempting to keep the divided diplomatic service together. A few days after his appointment, a Provisional Government was established. As Brennan did not support the Treaty he resigned as Acting Secretary of the Department of External Affairs in late January 1922. He was replaced by Walshe.

The aforementioned had little diplomatic experience but Brennan had recommended him. Harry Boland, the Dáil envoy to America, was dismissed in February 1922, a month later O’Kelly followed suit. Both opposed the treaty and had spread propaganda against the new government. Gavan Duffy had plans to expand the department but his hopes were dashed when the Irish Civil War began on the 28th June 1922.

He was also eager for Ireland to gain admission to the League of Nations and had predicted this would occur by September. However, an application was not possible until the Irish Free State was formally established. Eventually Gavan Duffy resigned in July 1922 over domestic policy issues. Walshe set about organizing the pro-treaty diplomats such as Michael MacWhite, Charles Bewley and Murphy. These men formed the core of the department. He also added a publicity staff which included Rosita Austin, Seán Lester and Francis Cremins.

Arthur Griffith was appointed as the Minister for Foreign Affairs for the second time in July 1922 but he died the following month on the 12th August. Michael Hayes, the Minister for Education, took over the post for a short time. In September, Desmond FitzGerald was given the position. FitzGerald had fought in the GPO during the Easter Rising and had been the Director of Publicity for the Dáil. During September, W.T. Cosgrave was elected President of the Executive Council. hen the Irish Free State formally came into existence on the 6th December 1922, FitzGerald became its first Minister for External Affairs.

The pro-treaty TDs eventually formed a new party Cumann na nGaedheal, which was formally launched in April 1923 and led by Cosgrave. Under FitzGerald, the Free State began to move away from a propaganda-based foreign policy. It is necessary for every nation to have an efficient and well-organized department of external affairs. However, many TDs believed that there was no need for a separate department to deal with this. Over the years though, Walshe transformed External Affairs into an indispensable government department.