By Hanna Philomena Hearne

Ireland of the late 17th and early 18th century was riven with poverty, hunger and destitution. There were, however, the comfortable families of the great houses of the titled descendants of the Planters. Ireland had gone through the throes of the Famine and persecution, but a tiny ray of hope began to emerge with the end of that era. Religious persecution eased; priests and religious slowly came to the fore.

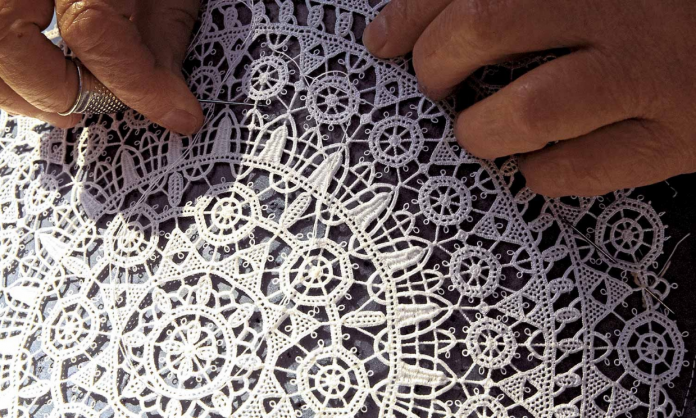

In 1833, a Carmelite order of nuns came to the town of New Ross in Co. Wexford. This was a contemplative order, yet they managed to contribute to the education of young people in their area, teaching lacemaking at evening classes.

This lacemaking craft flourished and soon the gentry became aware of it. Lady Aberdeen, wife of the Viceroy, came to New Ross to pay a visit to the Carmelites, and was impressed at the craft of lacemaking taught by the Sisters. Lady Aberdeen returned to Dublin and organised a Lace Ball to promote the craft of lacemaking.

Lady Aberdeen gathered together a committee to manage the sale, marketing and promotion of lace, and as a result, lace became a speciality of the wealthy. The nuns were making some money, which they reinvested in materials, and so the workers could be paid in cash every Friday. Many households had no visible means of support, and so this was a boon to women. It also gave them power, status and finesse.

Their wage was 15 shillings weekly, a woman’s wage at that time, but there were few women in the workforce.

New Ross needlepoint lace became very popular and desired by the upper classes. It was worn by royalty on their special occasions, and was incorporated into wedding dresses, christening robes and the vestments of the clergy.

There were other women of goodwill who tried to help young people, but the nuns were most successful. The Sisters in New Ross and the St. Louis Convent, Carrickmacross, had success, and lace flourished until the beginning of World War 1. That was the end of the overseas market. People who had learned the craft passed it on. In later years, a cooperative was set up in Co. Monaghan, and the lace craft was preserved. The greater changes for the general good came about from 1870.

They were slow in the beginning but education of the masses became a priority. Information and technology were still in their infancy. The craft of lacemaking spread to Co. Cork, Kenmare in Kerry, and on to Limerick. Nowadays, lace has earned its place in history and is preserved for generations.