By Alison Martin

Whilst many will have heard of the Italian inventor Guglielmo Marconi, relatively few will have heard of the name Frederick Sammis. For those familiar with the story of the Titanic disaster and the inquiries which followed, Frederick Sammis is probably best remembered for the role he played in helping to arrange the sale of surviving wireless operator Harold Bride’s exclusive story to the New York Times.

The circumstances surrounding this arrangement, along with the role that both he and the inventor Guglielmo Marconi played in this deal, were a point of great interest at the American Inquiry. Aside from references to this incident though, very little has been written about Sammis and his wider career. By examining a variety of sources however, it is possible to get a fuller picture of his life.

Born in New York in 1877, Frederick Sammis was the son of Theodore M. and Sarah Amelia Sammis (née Whitson). According to the 1880 U.S. Federal Census, his father then aged thirty-four, was a clerk. From a fairly young age, Sammis showed an interest in telegraphy. At the age of fifteen, he was employed by E.S. Greeley & Co.

This company, according to an advert in the New York Times, was a leading manufacturer, importer and seller of railway and telegraph supplies. By 1897, he was working for J.H. Bunnell and Co., which was a manufacturer of telegraph and other electrical supplies. As he was still relatively inexperienced at this stage, it is unlikely that he was involved with the technical work. The 1900 U.S. Federal Census listed him as an office clerk for an electrical supplier.

In July 1901, Sammis married Sarah Marsland Young. The couple would later go on to have four children. Sammis later stated that he had been associated with the Marconi Wireless Telegraph Company of America from mid-1902. He first joined as an assistant to the then chief, William Walter Bradfield. In this capacity, he helped to conduct a number of tests between stations at Sagaponack and Babylon, both in New York. By 1908, he had been appointed acting chief engineer whilst Bradfield was in London. Eventually in 1910, he was promoted to chief engineer.

In an interview published in Radio Broadcast Magazine in 1924, wireless operator Jack Irwin recalled that Sammis ‘occupied a similar position to Pooh-Bah, that extraordinary and versatile character in Gilbert and Sullivan’s Mikado.’ In other words, he acted in almost every capacity. When he was later asked about the extent of authority, Sammis stated that ‘my part of the business is to see that the ships are properly fitted, and the land stations are kept in good working order, and generally, I have to do with the technical side of the business, not the traffic; we have a separate manager for that.’ In 1910 wireless operator Jack Irwin, also recalled making a customary report to Sammis’ office, when he arrived in America after a voyage.

It was in the days following the sinking of the Titanic and during the subsequent American Inquiry, that Sammis was somewhat propelled into the spotlight. Senator William Alden Smith, who was leading the investigation, seemed very interested in uncovering details of how the New York Times secured the exclusive stories of Titanic’s surviving wireless operator Harold Bride and the rescue ship’s operator Harold Cottam. After the Carpathia had docked in New York, the Italian inventor and owner of the company Guglielmo Marconi, had gone aboard the Carpathia to meet Bride with a reporter from the New York Times.

This was no spur of the moment decision, as it would seem that there was a fair amount of planning behind this. During the investigation, Senator Smith had several telegrams read out which had been intercepted by the U.S. Navy. One read ‘Seagate to Carpathia: 8.12 p. m. Say, old man, Marconi Co. taking good care of you. Keep your mouth shut and hold your story. It is fixed for you so you will get big money. Do your best to clear.’

Another more specific message sent at 8:30 P.M. stated ‘To Marconi officer, Carpathia and Titanic: Arranged for your exclusive story for dollars in four figures. Mr. Marconi agreeing. Say nothing until you see me. Where are you now?’ The message was signed by J. M. Sammis. There were also other messages uncovered instructing Cottam and Bride to meet Sammis and Marconi at the Strand Hotel, when they arrived in New York.

Sammis eventually took responsibility for the messages. However, he was keen to emphasize that he had not been responsible for the wording but had telephoned the message to the operator at Seagate station, who had hastily compiled the message. Sammis defended his actions by stating the he had felt he was trying to do the poorly paid Marconi employees a good turn, by securing them a highly paid newspaper deal.

The Titanic’s surviving wireless operator Harold Bride had stayed at his post with the senior operator until the last minute and had survived by clinging to an upturned lifeboat. On the rescue ship Carpathia, Bride and Cottam had then worked almost beyond endurance in order to send the names of survivors to land. Bride later testified that he had received $1,000 from the New York Times, whilst Cottam received $750. Marconi was also questioned closely about the deal and Senator Smith eventually got him to agree that such a practice should be discouraged in the future.

In 1915 Sammis resigned from the Marconi Company. He later stated that he left because he could not get along with E.J. Nally, the Vice-President and general manager of the American Marconi Company. Despite his decision however, Sammis was soon able to move forward with his career. Around 1917 he was hired by The American Radio and Research Association (AMRAD).

Founded in 1915 by Tufts University graduate Harold Power, the company made radio receivers for the U.S. government in the lead up to American intervention in the First World War. When the U.S. formally entered the war in 1917, all amateur radio stations were shut down but Power continued to make receivers for the U.S. Navy. It was Sammis’ job to pilot AMRAD through the shoals of government contracting and for this he was payed handsomely.

Following the war however, it would seem that he changed occupations. The United States Federal Census of 1920, stated that he was involved in export work specializing in electrical goods. It would seem that he had entered the export field on his own accord. He did so with some success and by 1923 Sammis and Co. had secured the domestic and export representation of the Hall and Carey Weaving and Belting Co., formerly the Empire Manufacturing Co.

Having taken the next step in his career, Sammis eventually moved to Hollywood in order to work for RCA Photophone as their Pacific Coast Manager. RCA Photophone Inc. was a subsidiary of RCA, set up in 1928 in order to exploit the Photophone sound-on-film system. In his book Sarnoff: an American Success, Carl Dreher recalled that Sammis and David Sarnoff, one of the founding figures of RCA had initially clashed over engineering practices. By 1929 however, they had patched up their differences and Sammis had been put in charge of the Photophone plant in Hollywood.

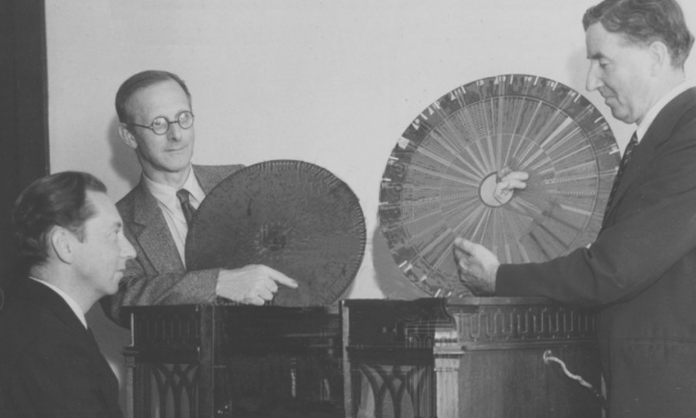

There are relatively few details on Sammis’ later life. In 1936 he invented ‘the singing keyboard,’ believed to be a precursor of modern samplers. Describing its potential, Sammis stated that ‘At once it will be evident that we have a machine with which the composer may try out various combinations of words and music and learn at once just how they will sound in the finished work.’ In 1940 he joined the Overseas Trading Corp, as resident agent in charge of the LA office. Sammis died in 1953 in Santa Barbara, Ventura, California.