By Eddie Bohan

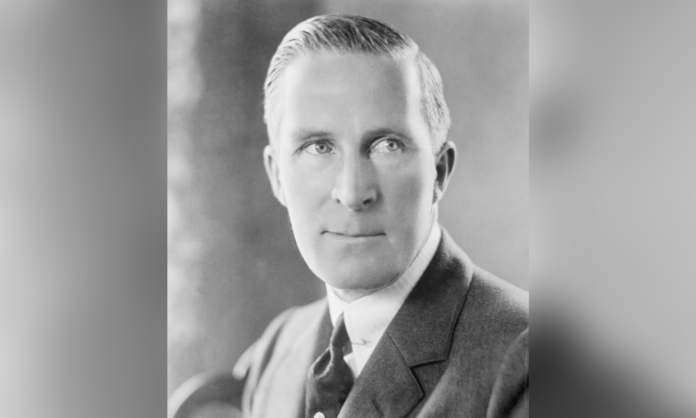

One hundred years ago, the killing of an Irishman from Athy Road, Carlow would not alter the course of the War of Independence or Civil War that engulfed a nation but would be part of a massive sea change of attitudes and rules that governed Hollywood. Born in 1872, William Deane-Tanner spent his early life living and being educated in Carlow but when he failed to qualify for the British military school at Sandhurst and follow in his father’s footsteps, he immigrated to the United States in 1891.

Ten years later he married an actress, Ethel May Harrison, and in 1902 his daughter Ethel Daisy was born. On October 22nd 1908, Deane-Tanner disappeared abandoning his wife and young child. With no contact from her husband, Ethel May obtained a divorce in 1912.

But far from being dead, the errant husband reappeared in 1912 in Hollywood, now known as William Desmond Taylor and began acting and later directing in silent movies for Paramount Pictures. Towards the end of the First World War, he joined the Canadian Expeditionary Force and was dispatched to France but by the time he arrived on European soil, the fighting was over. He returned to Hollywood and at a time when it was cheaper for studios to employ actors who were also good directors, Taylor began to make a name for himself.

He was known as a party host and a womaniser. His films were extremely successful and it was while watching one of these films that his ex-wife was able to point out to her daughter ‘that’s your father’ believing up to that day that he was dead. But his death would come on February 1st 1922 when at 7.30am his valet found him shot to death on the floor of his living room. He had been shot in the back but the body seemed to have been disturbed post-mortem. The course of the murder investigation would now take a muddy turn.

The murder was sensational news both in the United States and around the world including Ireland, as a number of young Hollywood starlets became embroiled in the torrid case. When the valet, Henry Peavey, found the body his first call was not to the police but to the studios and when the police eventually were summoned, the crime scene had been ‘sanitised’. He had been shot in the back while apparently sitting in a chair at his desk but when the police arrived his body was laid out on the floor.

The neighbours reported that they heard a bang, thought initially to be a car backfire, at 9pm the previous night but a flawed medical examiners report failed to pinpoint the exact time of death. The last person to see Taylor alive and initially the first prime suspect was actress Mabel Normand. A rising star of the silent era, she was the first person to throw a custard pie on screen and would also direct Charlie Chaplin in ‘Mabel’s Strange Predicament’, the first time that he would portray the tramp character that made him famous.

Her connection to the Taylor murder and the subsequent murder of her chauffeur, R.C. Greer, in December 1923 in front of her, effectively ended her career. Norman was exonerated when witnesses saw her drive away at 8.30pm having said goodbye to Taylor. Another early suspect was starlet Mary Minter, who had a crush on the director and had written some intimate letters to Taylor but these had disappeared by the time the police arrived. The involvement of these women and the rumours of orgies and drugs created sensational newspaper headlines.

Another prime suspect was a previously employed valet of Taylor’s, Edward Sands, who had been sacked for stealing from his employer and mysteriously the day after the murder disappeared. The L.A. District Attorney in charge of the investigation, Thomas Woolwine, concentrated a lot of police resources on finding the missing valet but he was never found. There was newspaper speculation that he had sent the police a confession before boarding a ship in New England and heading to Europe but this was believed after to be a misdirect planted in the newspapers by Woolwine.

By the time of his death, Taylor had appeared in 27 films and directed a further sixty. There were stories that his murder was a mafia hit that was drug related or a jealous lover or a jilted husband. Yet another prime suspect was Mary Minter’s mother Charlotte Shelby, a controlling socialite who appeared to be having an affair with DA Woolwine. Woolwine’s investigation was meandering and he would later be found guilty of embezzlement and political corruption.

The case today remains unsolved; in Sidney Kirkpatrick’s 1946 book ‘Cast of Killers’ no conclusion was drawn but the film maker King Vidor who heavily researched the story for a possible film, concluded that the most likely killer was Minter’s mother Shelby who was annoyed the Taylor was not helping her daughter more in the industry and that it was her relationship with the DA that helped cover up the crime.

In 1930 the case continued to make headlines when Russell Rinaldo confessed to the police that he had killed the Irishman but after a lengthy investigation no case was proven. There were several deathbed confessions by actresses including Patricia Palmer in 1964. There have been, just like the Kennedy assassination, endless theories and conspiracies even a regular newsletter known as ‘Taylorology’ published regularly by Bruce Long. It was Taylor’s sensational murder and the previous trial of Fatty Arbuckle for rape, which forced liberal Hollywood to clean up its act.

To pre-empt the planned federal legislation cleaning up Tinseltown, the major studios came together and created a code of conduct that self-censored the industry, known as the Hays Code, named after William Hays. The code prohibited profanity, suggestive nudity, graphic or realistic violence, sexual persuasions and rape.

One final plot twist come courtesy of the film website, IMDB. According to Desmond’s biography page he had an eight-year affair with a set designer George Hopkins until his death in February 1922.