By John Scally

It is almost thirty years ago since I first met him but I remember the day as if it was yesterday. As a young student just completing my Ph.D. I was nervous. I was speaking at my first conference to a gathering of psychiatrists. I was only there because their first choice to speak was unavailable.

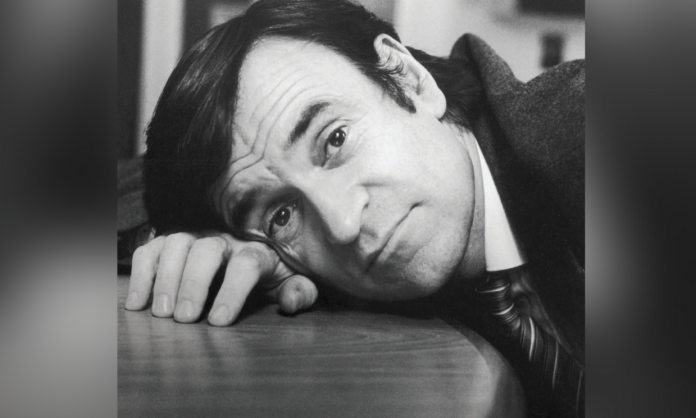

However, the reason I was so nervous was because I had to speak on the same platform as a giant of broadcasting and psychiatry Professor Anthony Clare. I can still see him walking in the door because there was a collective intake of breath. We all were awestruck because we had this household name in Ireland and the UK in our midst.

After my contribution he spoke next. He generously began his speech by referring back to something I said about the importance of asking the right questions. When we spoke afterwards about that issue he was tickled about a quotation I shared with him of Karl Rahner: ‘The central question is: what is the central question?’ We corresponded afterwards and each letter from him was a window into one of the most brilliant minds of his generation.

Born in Dublin in 1942 he was the best known psychiatrist of his generation. His BBC Radio 4 show, ‘In the Psychiatrist’s Chair’, which ran from 1982 to 2001, brought him international fame and changed the nature of broadcast interviews forever.

Mental Health

Thankfully it has now become acceptable to speak about mental health in Ireland. However, long before it was fashionable to do so in his role as Director of Saint Patrick’s Hospital Anthony Clare campaigned vigorously for the rights of disabled people.

He did do because he believed he was talking about the rights to which all citizens of this land are entitled. He had a burning desire to build more public awareness of the needs of people with psychiatric illness. He felt they needed to have a voice in the community and their requirements should not be put on the long finger.

He felt that a number of questions presented themselves about the place of such patients. In Irish society, are all people equal, or are some, like the disabled, seen as less equal than others? How many are institutionalised? How many have a home of their own? How many have access to the special education that they may require?

How many have a job? His blood boiled when he thought of all the indignities some of his patients had been subjected to, such as people forced into demeaning conditions in ‘mental hospitals’ known as ‘the madhouse’ and ‘the human hell’. Such places were generally in Ireland intimidating buildings, monstrous, ugly, brooding and profoundly sad. They were full of people with tragic stories.

The hospital was seen as serving three functions in the community; detention, retribution and deterrence. It kept people judged to be dangerous out of circulation, it punished those who transgressed conventional mores and it kept people from straying off the narrow path, otherwise they might face a fate worse than jail, incarceration in ‘the madhouse’. Nobody really believed that anybody went there to be healed.

Every time relatives went to visit loved ones in these hospital they shivered. The most chilling part of the unpleasant ordeal was the sound of the rustling of keys as the ‘inmates’ were locked in their cells. The keys were symbols of power and authority for the nurses, but for the patients they were a constant reminder of their subservience.

Although families struggled with the courage of lions with their loved one’s disability they were not able to readily cope with mental illness. People could not bring themselves to use the words ‘mental illness’ but the odium was obvious even when the comments were relatively mild.

In rural Ireland in particular appearance and reality seldom coincided. At the very bottom of the human scrapheap were those who suffered from mental illness. Just one step up was their families, with members of the travelling community at more or less the same level. A determined campaigner Anthony Clare was willing to fight to the bitter end.

He felt that part of the problem is that for too long the focus when it came to the disabled was on charity. One of the big advances that has finally happened is that people now see disability issues as questions of justice and rights.

He found no villains anywhere. On the contrary one could not be but impressed by the hard work and dedication of those in charge of the services. How could so many honourable people who were undoubtedly charitable and competent, allow such a situation to develop? One of John B. Keane’s creations, Dan Paddy Andy O’Sullivan famously said, ‘You’ll never have peace in this country until every man has more than the next.’

Anthony Clare felt that we had reached that stage. While the strong prevail the weak are just thrown out to the side. We are so conditioned to reward the strong and penalize the weak that we do not take the time to ask why was the person weak in the first place. No other question dominated his thinking.

Gone but not forgotten

It came as a huge shock in 2007 to hear of his sudden death. I immediately thought of the words of the late American poet Mary Oliver When Death Comes:

When it is over, I want to say: all my life

I was a bride married to amazement.

I was the bridegroom, taking the world into my arms.

When it is over, I don’t want to wonder

If I have made of my life, something particular and real.

Anthony Clare was ‘married to amazement’. He made it his mission to see life through ‘the windows of wonder’. Anthony Clare embodied one quality more than anyone I know: intellectual curiosity. In our era of ‘fake news’ his message is a call to arms. It is an exhortation to intellectual rigour.

He had an intuitive understanding that precedents from the past do not provide answers to questions never asked in the past. However, without the appropriate debates and discussions, it might be argued that we are at the risk of threatening our very humanity.

While he dedicated his life to medicine he was keenly aware that it raised a plethora of difficult questions. Rather than waiting for problems to arise and resorting to crisis management he felt it would be more constructive to have adequate safeguards in place to ensure that people’s integrity will not be trampled on. As any doctor will tell you prevention is better than cure.

We cannot let the complex new questions in medicine and elsewhere be settled by default. Anthony Clare’s greatest legacy is his call to humanity to ask the central questions. Irish life is much poorer for his passing.