By Kenneth McNally

Once upon a time…….well yes, it happened many years ago; but this is no whimsical fairy tale, rather the little-known story of how Ireland’s great legendary warrior inspired an American President and became a frequent topic of conversation in the White House.

As the nineteenth century drew to its close, the Irish literary revival had taken hold in the national consciousness. Its origins lay in the work of two dedicated Gaelic scholars, John O’Donovan and Eugene O’Curry, whose copious translations of archaic mediaeval manuscripts in the collections of the Royal Irish Academy had unleashed incredible tales of a shadowy world of epic events, peopled by a fearless breed of demi-god warriors.

Soon modern writers began to mine this rich vein of material to produce a plethora of books and articles on early Celtic Ireland, often featuring Cúchulainn as the hero-protagonist. Foremost among these new storytellers was Standish James O’Grady, an inveterate romantic whose succession of volumes invoking the valorous imagery of a distant mythological age capitalised on the growing public appetite for this brand of popular literature.

Arguably the most influential was the publication to the ever expanding Cúchulainn franchise was the publication in 1902 of Lady Gregory’s ‘Cuchulainn or Muirthemne’, hailed by Yeats as the greatest book to have come out of Ireland. It wasn’t quite that, and the claim would not go unchallenged, but the book was generally well received and won many plaudits and admirers at home and abroad. The playwright J.M. Synge remarked: “I had no idea the book was going to be so great.” and Mark Twain, in a letter to Lady Gregory to express his delight with the stories, added: “We cannot thank you enough for making it possible for us to read them.”

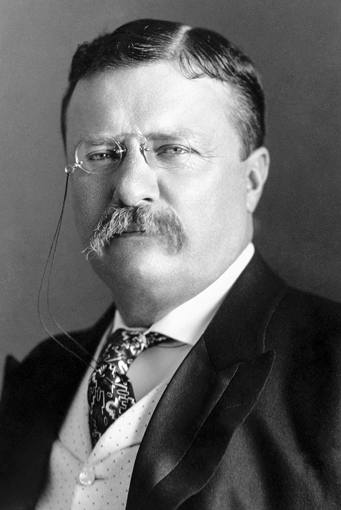

Further meaningful endorsement would come from a seemingly unlikely quarter. Theodore Roosevelt, twenty-sixth President of the United States, was enthralled by Lady Gregory’s book and is said to have kept a copy at his bedside as a welcome distraction from the pressure of high office.

That Roosevelt should have identified closely with these picaresque tales is not in fact surprising, given his larger that life character. An indefatigable man of action with a gung-ho attitude to life and an insatiable zest for adventure, he had distinguished himself militarily when, as colonel of his intrepid Rough Riders bridge, he led the charge to relieve Santiago in Cuba, effectively bringing to an end the Spanish-American War, making him a national hero and a sure-fire candidate for the country’s top job.

Then of course there were those famous and much publicised bear hunts in the wild, earning him the affectionate nickname ‘Teddy’, to the delight of newspaper cartoonists and a boon for teddy bear manufacturers. Brusque in manner with little patience for small talk, he was regarded as something of a roughneck by political opponents, one of whom on hearing of Roosevelt’s electoral victory, exclaimed in exasperation: “I can’t believe that damned cowboy has been elected President of the United States!”

If the cowboy tag stuck, it belied an incisive intellect and an erudite cultural awareness. Roosevelt’s regular lunch breaks with an eclectic mix of guests in the White House were invariably lively affairs, when the topic of conversation was just as likely to be the Cúchulainn saga as the economy, politics, theatre or football. During these gatherings the President would often jump up from his chair, gesticulating wildly to emphasise a point under discussion.

In 1906, Roosevelt, then in his second term of office, was invited by the influential ‘Century Magazine’ to contribute an article of his choice for publication the following January. It came as no surprise that his subject would be ‘The Ancient Irish Sagas”.

Already a highly successful author, he was clearly in his element with this commission, penning a long scholarly essay that demonstrated his enthusiasm for the subject. In his discussion of the epic ‘Ulster Cycle’ he writes:

‘ …the most interesting of these is the Cúchulainn cycle. The poems which tell of the mighty feats of Cúchulainn, and of the heroes whose life-threads were interwoven with his, date back to a purely pagan Ireland cut off from all connection with the splendid and slowly dying civilization of Rome, and Ireland in which still obtained ancient customs that had elsewhere vanished even from the memory of man.’

To illustrate the piece, ‘Century Magazine’ commissioned one of America’s foremost graphic artists, J.C. Leyendecker, who rose splendidly to the occasion with a stunning full-colour portrayal of Cúchulainn riding into battle, resplendent in the imagined garb of a Celtic warrior, driven by his faithful charioteer. The image is of course subjective and owes much to artistic licence; but no matter, Leyendecker had fulfilled his task with panache, and for good measure included a sultry portrait of Cúchulainn’s arch enemy, Queen Maeve.

Shortly afterwards, black and white reproductions of these illustrations appeared in a Dublin pamphlet published by the Catholic Truth Society of Ireland. Written by a Tralee priest, Fr. A.M. Skelley, it told the Cúchulainn story in abridged form for the masses, selling at an affordable one penny.

Roosevelt’s preoccupation with the sagas was much more than a private passion. He saw it as his mission to communicate the extraordinary breadth and beauty of this ancient literature to a wider audience, and admonished education authorities for neglect in this regard: “It is greatly to be regretted,” he wrote, “that America should have done so little either in the way of popularizing and familiarizing that literature.” He spoke out on the subject on numerous occasions, and urged the establishment of chairs of Celtic study in the country’s leading universities. In this aspiration he was ahead of his time.

From childhood, Theodore ‘Teddy’ Roosevelt had been an avid reader, particularly of derring-do adventure stories, immersing himself in “inspiring chronicles of men who were fearless in battle”. Now, in the high-octane persona of Cúchulainn he found an erstwhile kindred spirit.